Accepted by The Quarterly 1994, made it to galleys, magazine folded before publication. Copyright 2024 by Tetman Callis.

Hobbs is a spooky little town at night. Roughnecks drive around in pickup trucks on streets that are otherwise too empty underneath traffic signals that early in the evening switch from the green-yellow-red cycle to flashing stops or cautions all around. People, men and women both, hang out in parking lots or alongside filling stations, the people looking like they’re so tired of waiting for something to happen that they’ve decided to go out and see if they can make anything happen before it gets too late.

In the daytime, the people are quite sweet, and there are some lovely honeys here, as everywhere. Business brings me here. Tonight I go back home, by tiny two-engine Beechcraft prop job flown by an outfit that calls itself an airline and has pilots sporting boards with gold stripes on their shoulders, and looks on their faces that suggest they are aware that other fellows with similar epaulets are flying faster, bigger, noisier aircraft further up in the sky.

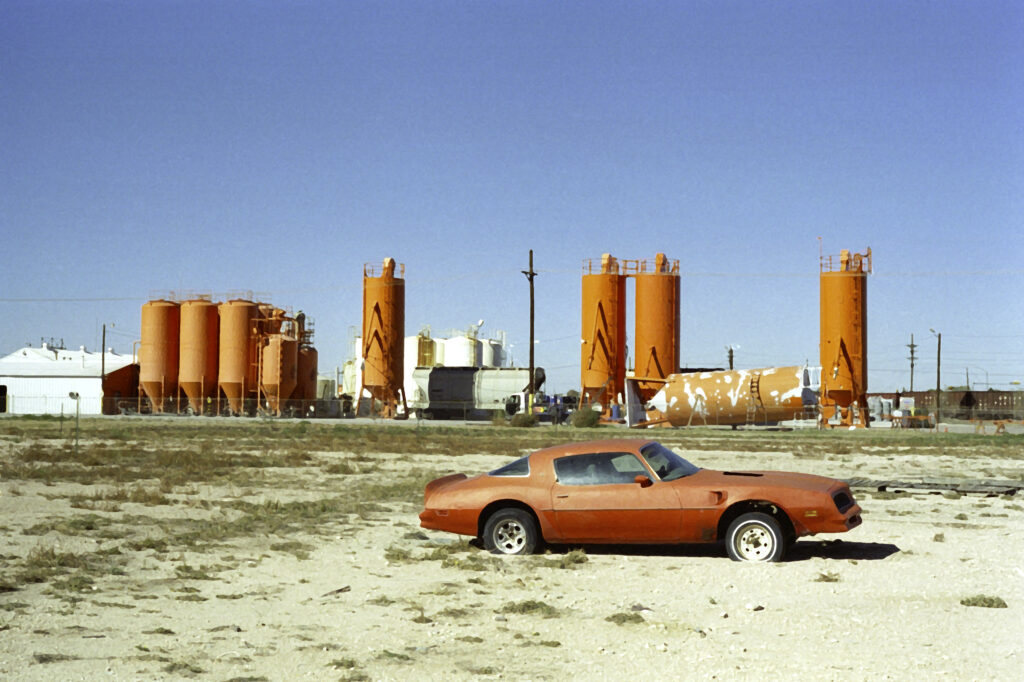

These are good people here. On Election Day, they put out national flags on poles that fit into sockets in the sidewalks of streets with names like Broadway and Bender and North Grimes. This is an oil town, the kind wherein “oil” is pronounced as a one-syllable word and a bank vice-president asks me if my accent is from Connecticut.

“Ohio,” I tell him.

They’ve set me up in a nice apartment here, in a building owned by the fellow who seems to own most of what they call Downtown Hobbs. They’ve told me this building used to be a movie theater. My apartment overlooks, from no great height, Carrie’s Ceramic Chaos, in the shop windows of which, at night, lighted ceramic trinkets winkle and flash. Beyond Carrie’s is The Kensington, “Assisted Living”—”The old folks’ home,” the bank vice-president said.

My business isn’t to be out on the streets at night, but I’ve been working late, then going for a spin in my nifty rental car after I knock off for the evening. That’s how I know about the roughnecks and the parking lots, and about how the girl at the Baskin-Robbins wipes the pint container of ice cream clean against the belly part of her black t-shirt.

The roughnecks frighten me, but only in prospect. They are the kinds of fellows who, when they were in high school, used to come down to El Paso and kick the crap out of our city-boy football teams. Now they work the rigs and appurtenances, wrestling with huge, heavy, dense pieces of steel, and with fluids and gases under the pressures brought down by being trapped under many hundreds of feet of the earth’s crust (which has a crustier appearance here than it has in greener places). From time to time, a roughneck or two gets roughed up or even killed outright in some gruesome fashion through an unfortunate conjunction of these high pressures and heavy equipments.

Old men in feed caps, work shirts, jeans and heavy boots talk about such goings-on in Casey’s Diner, where I go for breakfast and which is in a building also owned by the fellow who owns this one where my apartment is with its nice furniture where I sit and contemplate now. My business isn’t to be out on the streets at night, but to be in the old, abandoned bank building by day, so after I have my Cholesterol Zoomer breakfast—sausage and cheese omelette with buttered toast—I walk across Broadway and set to work. We keep the documents I work with in one of the vaults, “to protect them against fire,” the bank vice-president said. Who would want to burn them I can only guess at, but accidents happen, and as one of my bosses back in Albuquerque said last week, “We’ve thrown half these people out of work and sued all their brothers-in-law.” So I lay low and do my work.

The vault also contains what must be all or a substantial fraction of the gun collection of one of the bank’s owners, and there are boxes of ammo, too. Several people from the bank told me, “Don’t touch Bob’s guns; they’re loaded,” and I don’t doubt that they are, but I wouldn’t touch them in any case, as a man does not touch another man’s guns uninvited. I looked and counted, and there are at least enough of them to outfit two squads of light infantry. What a fellow needs with so many guns is beyond the means of a city-boy like me to figure out.